The insights page is the place where the index team and the OK network share their findings and learnings from the Global Open Data Index (GODI). We do so to record outcomes, share knowledge and to create a discussion about issues that are important to the open data community.

This is Open Knowledge International’s first State of Open Government Data report. Based on key findings from our work on the Global Open Data Index (GODI) 2016/17 it outlines the obstacles to open government data publication, and suggests steps that will allow progress in the field of open data.

The report identifies three problem areas: 1) Data is hard (or even impossible) to find online, 2) data is often not readily usable, 3) open licensing is rare practice and jeopardised by a lack of standards. As such, institutions are producing information which is encoded in forms that are preventing data publishers and public users from communicating with one another.

We propose that dialogue is critical to produce relevant data that can be used by civil society and GODI - more than only a benchmark - provides the platform for this dialogue. For GODI 2016/17, we ran a public dialogue between governments and data users for the first time to foster the production of meaningful data.

The learnings and outcomes from this process are documented in our final report. It also explains important variables to further elaborate this dialogue model. The report is open to debate in order to continue learning from your experiences. We would love to hear your feedback in our discussion forum.

The GODI 2016/17 Report is also available in Turkish.

Data findability is a major challenge. We have data portals and registries, but government agencies under one national government still publish data in different ways and different locations. Moreover, they have different protocols for license and formats. This has a hazardous impact - we may not find open data, even if it is out there, and therefore can’t use it. Data findability is a prerequisite for open data to fulfill its potential and currently most data is very hard to find.

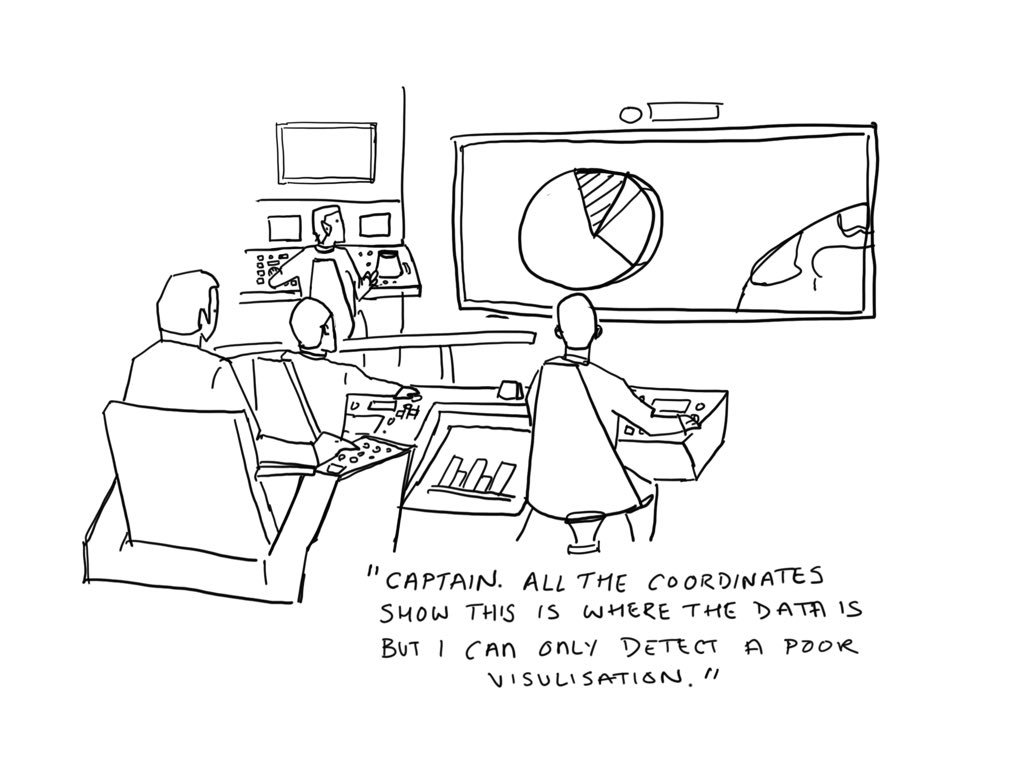

A lot of ‘data’ IS online, but the ways in which it is presented are limiting their openness. Governments publish data in many forms, not only as tabular datasets but also visualisations, maps, graphs and texts. While this is a good effort to make data relatable, it sometimes makes the data very hard or even impossible for reuse. It is crucial for governments to revise how they produce and provide data that is in good quality for reuse in its raw form. For that, we need to be aware what is best raw data required which varies from data category to category.

Open licensing is a problem, and we cannot assess public domain status. Each year we find ourselves more confused about open data licences. On the one hand, more governments implement their unique open data license versions. Some of them are compliant with the Open Definition, but most are not officially acknowledged. On the other hand, some governments do not provide open licenses, but terms of use, that may leave users in the dark about the actual possibilities to reuse data. There is a need to draw more attention to data licenses and make sure data producers understand how to license data better.

GODI is a platform to spark debate about open data. Ultimately, the Index is only relevant and actionable if it resonates with civil society and government. Thus, the Index seeks to enable meaningful dialogue about government data publication. Which regulations and laws prevent data from being published? Which government procedures block open data release? Why does individual data matter for different publics? And how to align the priorities of the public with those of government? More than being a poor ranking, the Index is a unique platform for citizens and governments to get into dialogue with one another.

####Themes **Contracting and procurement

Data findability is a major challenge. We have data portals and registries, but government agencies under one national government still publish data in different ways and different locations. Moreover, they have different protocols for license and formats. This has a hazardous impact - we may not find open data, even if it is out there, and therefore can’t use it. Data findability is a prerequisite for open data to fulfill its potential and currently most data is very hard to find.

A lot of ‘data’ IS online, but the ways in which it is presented are limiting their openness. Governments publish data in many forms, not only as tabular datasets but also visualisations, maps, graphs and texts. While this is a good effort to make data relatable, it sometimes makes the data very hard or even impossible for reuse. It is crucial for governments to revise how they produce and provide data that is in good quality for reuse in its raw form. For that, we need to be aware what is best raw data required which varies from data category to category.

Open licensing is a problem, and we cannot assess public domain status. Each year we find ourselves more confused about open data licences. On the one hand, more governments implement their unique open data license versions. Some of them are compliant with the Open Definition, but most are not officially acknowledged. On the other hand, some governments do not provide open licenses, but terms of use, that may leave users in the dark about the actual possibilities to reuse data. There is a need to draw more attention to data licenses and make sure data producers understand how to license data better.

GODI is a platform to spark debate about open data. Ultimately, the Index is only relevant and actionable if it resonates with civil society and government. Thus, the Index seeks to enable meaningful dialogue about government data publication. Which regulations and laws prevent data from being published? Which government procedures block open data release? Why does individual data matter for different publics? And how to align the priorities of the public with those of government? More than being a poor ranking, the Index is a unique platform for citizens and governments to get into dialogue with one another.